At a recent lesson I noticed the above statements at the top of my student’s assignment. I remembered writing these words, but a week later stared at them as my student warmed up, startled by how directly they spoke to my own practice. My approach to practice is changing because it needs to as I get older, and as my playing changes so does my teaching.

My practice needs to change because I seem to be more nervous about performing these days. My fingers are likely to feel anxious and unsure with material that I haven’t prepared exceedingly well, whereas in the past they would have more confidently sailed through. My current theory is that a loss of innocence that comes with maturity is the increased awareness of what we don’t know.

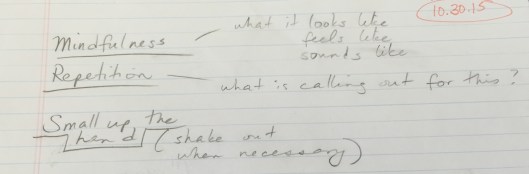

These three ideas help me focus my attempts to override nerves. First idea: It’s surprisingly easy to do things we are accomplished at without thinking, and we need to counter this tendency to be comfortable in performance. If I’m not mindful of what the positions look like on the keyboard under my hands, what they feel like as my hands and fingers fit in their hundreds of unique places within a given piece, and what the music sounds like…well, I’m sunk. I need to notice these things with a high degree of consciousness when I’m playing alone to be secure with the material when under the pressure of others listening.

Second idea: If I’m not paying attention to what in the music is calling out for repetition, I’m sunk again. It all needs lots of repetition to be secure, but there are sections, some very small, that need an absurd amount of repetition to be really known, especially in nervous conditions.

The third idea is more elusive, referencing a phrase I remember from my childhood. When my family lived in Kingston, Jamaica, we sometimes took “mini-buses” (large vans) as public transportation. A mini-bus would typically look impossibly full as it approached the bus stop, but the driver’s assistant hanging out the door gestured for us to climb on and would holler, “Small up yourselves!” to those already in the seats and in the aisles. Sure enough, more room could be made.

At the piano it’s easy to let tension settle in the hands, and some of the demands of the music require the hand to linger in an awkward stretch. The natural state of the hands when we shake them out and let fall at our sides is quite supple and compact, and the more we maintain this as we play, the better. Reminding myself and my students to “small up the hand” is now a familiar technical point of reference.

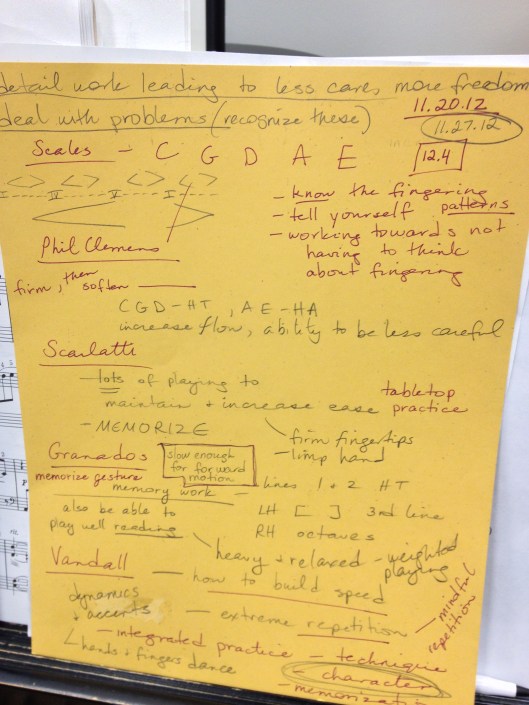

It amazes me how much I keep learning about playing and teaching piano, after some 20+ years of active work in the field. This month most of my individual practice has been for a temporary job at a church that integrates the keyboard into its service in a way I find very rewarding. When I think back on big pieces I played in my twenties, the shorter form classical works and hymn arrangements I’m practicing now can make me feel apologetic. I scold myself when I feel this way, because this music contains the essence of all I have learned to do – evenness, clarity, voicing, phrasing, articulation, characterization – and deserves my best effort.

Now in my mid-forties, these pieces that aren’t as difficult as the big pieces I played more than two decades ago can still be plenty demanding. At the piano it’s maddeningly easy to crash into a wrong chord or to stumble through a run. I have to ask myself more honestly where the music is calling out for repetition. And I have to pay better attention to my body, to keep it relaxed and to find the fingerings and maneuvers that allow my hands to stay in their naturally small and relaxed state.

Since the blog started as a project about Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier Book One, I’ll close by verifying that I’m still working on this. On a good day I am obedient to the daily plan I have for the Bach, which is to review a set of four preludes/fugues assigned for that day. They are all in my fingers now to varying degrees of comfort. They need a lot of time to settle and develop, more time for mindfulness, more repetition where it is called for, and more discovery of how a small and relaxed hand can make the work of playing Bach look, feel and sound easier than it is.