The older I get, the more I know what I don’t know. In high school and college I played piano with a clueless bravado that allowed my fingers to fly confidently over notes my brain did not fully understand. Somewhere along the way I became a good sight reader. Was it those adolescent years in Kingston, Jamaica where I had more free time to practice? Was it the high school choir accompanying I eagerly did? My piano teacher in high school required regular playing from the hymnal — did this make me a good sight reader? Did it have anything to do with my constant intake of the written word? The mysteries of why some pianists become good sight readers of Western notation and why others (often some of the best musicians) need more time to absorb the page in front of them are an ongoing hot topic in music pedagogy circles. Good research is pointing the way to a combination of experiences and strategies.

However the mysteries are solved or remain, I better understand the downfalls of my sight reading abilities and sometimes wish I read less well. In college I was greatly challenged and wonderfully taught, and I played a lot. But, perhaps in part because there was not enough struggle to read those notes, my knowledge became technical fairly quickly and theoretical awareness rarely surfaced in my individual practice. My moment of truth (I think each musician has one) occurred in the spring semester of my junior year when I crashed and burned in a public performance of a Beethoven Sonata movement (it was Op. 10 No. 3, movement one, if you must know). I had played it through from memory many times on my own and in front of my teacher, but I didn’t really know those notes on an cognitive level. I went into the high-stakes environment with an unfamiliar feeling of unease, perhaps finally mature enough to be subconsciously aware that other ways of knowing weren’t there to reinforce the motor-muscle memory in the fingers. The disaster and ensuing tears of mortification led to some of the most important conversations I had with my professors and began a turning point in how I practiced. The innocence of clueless bravado lost, a new path was needed.

And yet, this turning point seems to be one of the longest curves of my life. Now more than twenty years later, I still struggle to really know. Today while practicing Bach’s delightful fugue in A major from WTC book one I felt that familiar learning-too-quickly habit take hold, the notes coming easily and my fingers and ears giddy with what they were doing and hearing — too much intake, too fast, without enough struggle to understand. Of course the brain can’t be truly bypassed in this situation, and enough repetitions will eventually result in some actual knowing. But, if I bypass the knowing struggle as my fingers weave their way through the material, I’m only inviting future trouble. So, I keep working at deepening the ways in which I know the music, in essence making sure the struggle is early in the process rather than late.

Here are the ways of knowing I now try to activate. (These ideas are gathered from my teachers, my students, and various readings, but were particularly solidified when I read Geoffrey Haydon’s chapter “Memorization via Internalization for the Intermediate Student” in Creative Piano Teaching by Lyke, Haydon, and Rollin, 2011.)

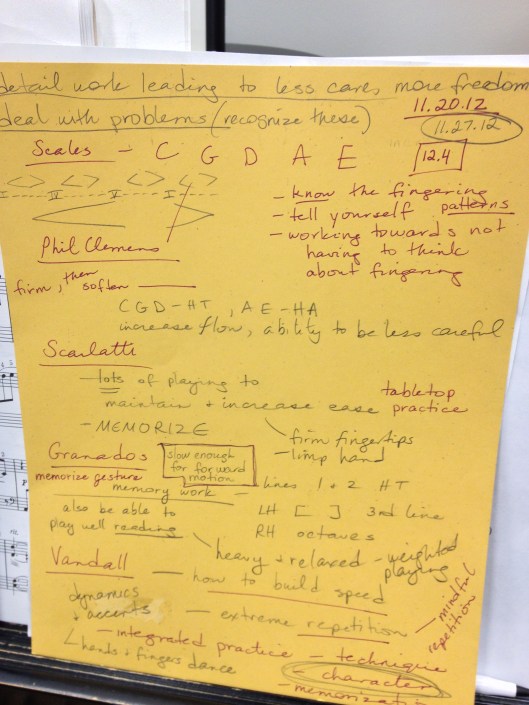

1. There is the technical knowing, which I value more and more for its importance as I get older, even as I recognize it was too often my only route of knowing back then. My fingers need more accurate repetitions than ever, to really have it. I’m better at recognizing where they are close to faltering even if I can get through that moment, because under just a little bit of pressure, stumbles will happen in those places. There is no room for doubt in my fingers.

2. There is the theoretical knowing, which can seem overwhelming (so many notes!) until I remember that theory is any way of naming what I am doing. I need ways of talking about musical passages, of identifying beginnings, middles, and endings. Western music theory is my best path for this, even if I name a passage as simply as, “The place where the hand does the back-and-forth thingy with the E major triad.” I have to be able to talk my way through an entire piece in one way or another.

3. There is the visual knowing, which has two parts. First, I am increasingly aware of the photographic memory that develops when I’ve read a page of notation so many times. (This is a useful way for me to review my knowledge, though not what I want to focus on in a memorized performance). The other visual is recognizing and knowing the way my hands look on the keyboard when playing a given passage — the amazingly diverse topography found within those black key groups surrounded by just seven white keys. Away from the piano, I find time to picture myself playing the piece; where I lose the view are places I need to better reinforce in my practice.

4. There is the aural, the knowing of the ears. I’m learning to sing various melodic lines and practice improvisation on the patterns and harmonies from the music I’m learning. Being able to trust my ears and improvise my way out of a trouble spot helps me integrate what is written. In the same way I envision myself playing the keys, I close my eyes away from the piano and hear my way through a whole piece to check my aural knowing.

And, finally:

5. There is the body’s way of knowing. Awareness of the physical gestures in use is an important part of this. I am trying to pay attention to how different mechanisms are at work as the body plays various passages, from the feet to the sitz bones to the shoulders, head, face, arms, and fingertips. Exploring and refining what feels best as the body experiences the music helps helps me recognize and trust the body’s knowledge of the musical experience.

Two final connections.

Until the most recent general education revision, the liberal arts curriculum at my college required each student to take one of two Bible courses — either Reading the Bible or Knowing the Bible. In my advising sessions I often needed to remind myself that Reading the Bible was for students with previous biblical study background; it seemed to me that the other way around made more sense — that the more advanced course would be Knowing the Bible. Our Bible/Religion department’s rationale was that you cannot read the Bible until you know how this canon was formed and organized. Reading the Bible went much deeper into content and interpretation, and was for students who already understood the structure of the volume of books and how to approach a reading encounter with it. This paradigm reminds me that much knowing goes into reading. I know a lot already to be able to sight read music well, and it is a vital skill in my line of work. Knowledge makes reading possible. Repeated and mindful reading of any text leads to greater insight and satisfaction.

Recently I’ve noticed a change in how I respond to a familiar comment from students in their lessons. “But I know this. I don’t understand why I’m not playing it better here.” In the past I used this as an opportunity to explore nervousness and how to play through it. Now, recognizing that insecurity about knowing (knowing what you don’t know) is often the main source of anxiety in performance, I respond, “You must not know it as well as you thought. Let’s look at how you can practice so you know it exceedingly well, in a lot of different ways, and we’ll see if that makes a difference.”

I am still one who needs this lesson the most.